Design-Disegno

Book

Design/Disegno, Geometry Measure and Algorithm for architecture and the city

Year: 2018

Ed Maggioli

Abstract

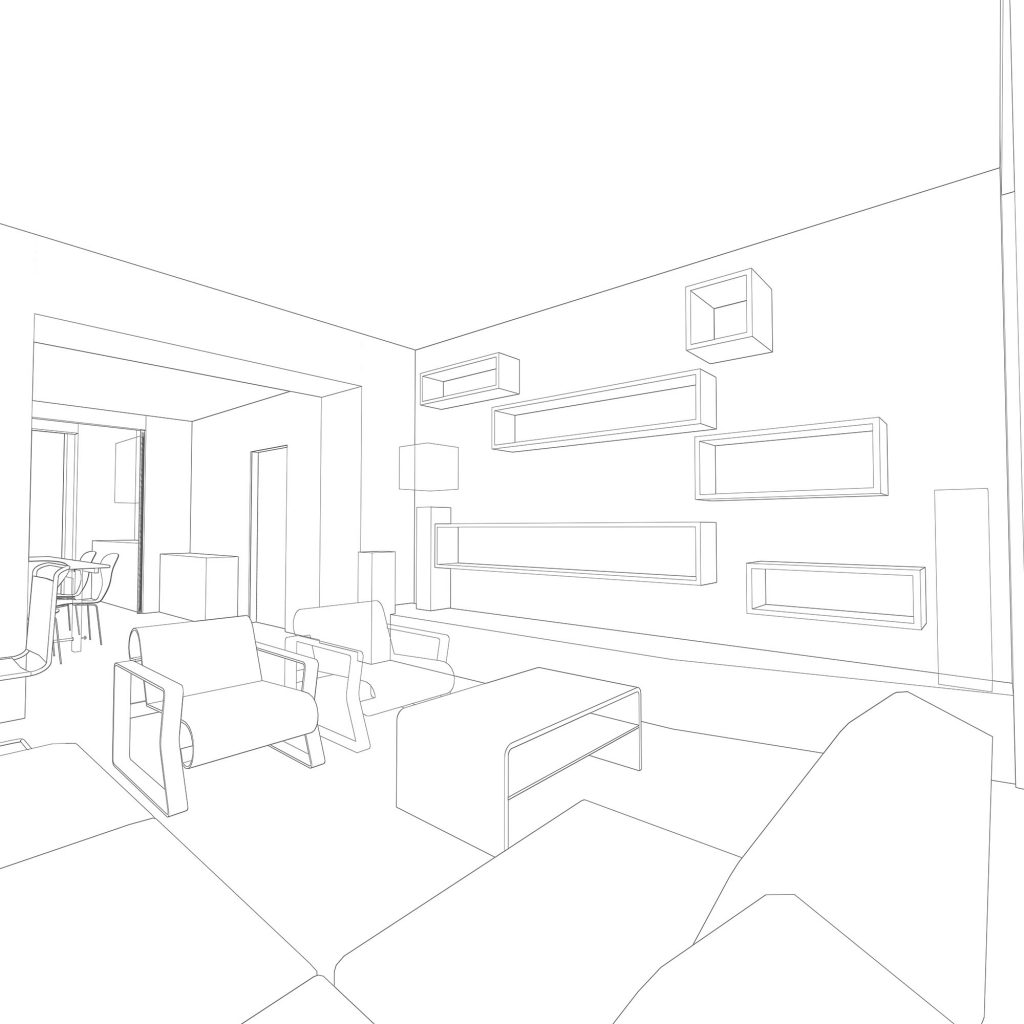

In a design process, the drawing (disegno) of an object or a space is the act of representing that thing with the idea of knowing and modifying it, and it is surely an essential moment.

It is an operation that requires a synthesis capable of projecting and confronting on a two-dimensional surface – physical or virtual – the complexity of the world with an idea of form.

The concept of measure and measurement is therefore, for the designer, the instrument that makes it possible to make an object, architecture or a urban fact representable, abstract, knowable and therefore designable. Similarly, for the user of that space, the measurement will help to memorise, map and place him in relation to it.

Mathematics and geometry, particularly in Western architectural culture, have played a fundamental role in enabling this knowability. The machine of the two mirrors invented by Brunelleschi opened up the definition of the rules of perspective and performed the compression of a three-dimensional world regulated by numbers, on a two-dimensional surface. Thus, it allowed the definition of a bijective (one-to-one) relationship between the drawn and the real world. This operation reinforced the distinct role of the tactile and the visual dimension – the stage and the scene – and permitted to describe and graphically think of infinity and the infinitesimal.

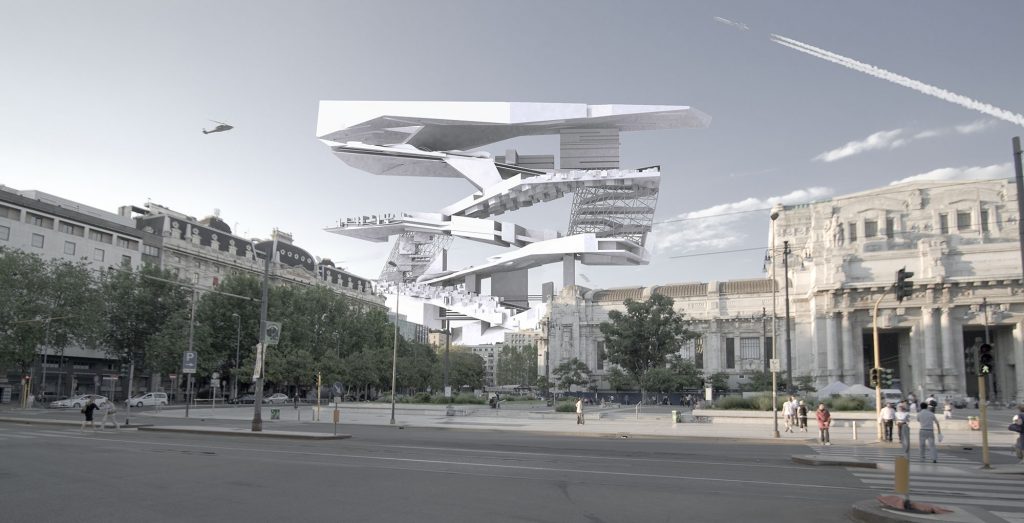

Towards the end of the last century, Frank O. Gehry created his machine to “see and know” what he had manually modelled. He developed a digital tool that would help to study and refine, on a screen, the folds made on his cardboard models.

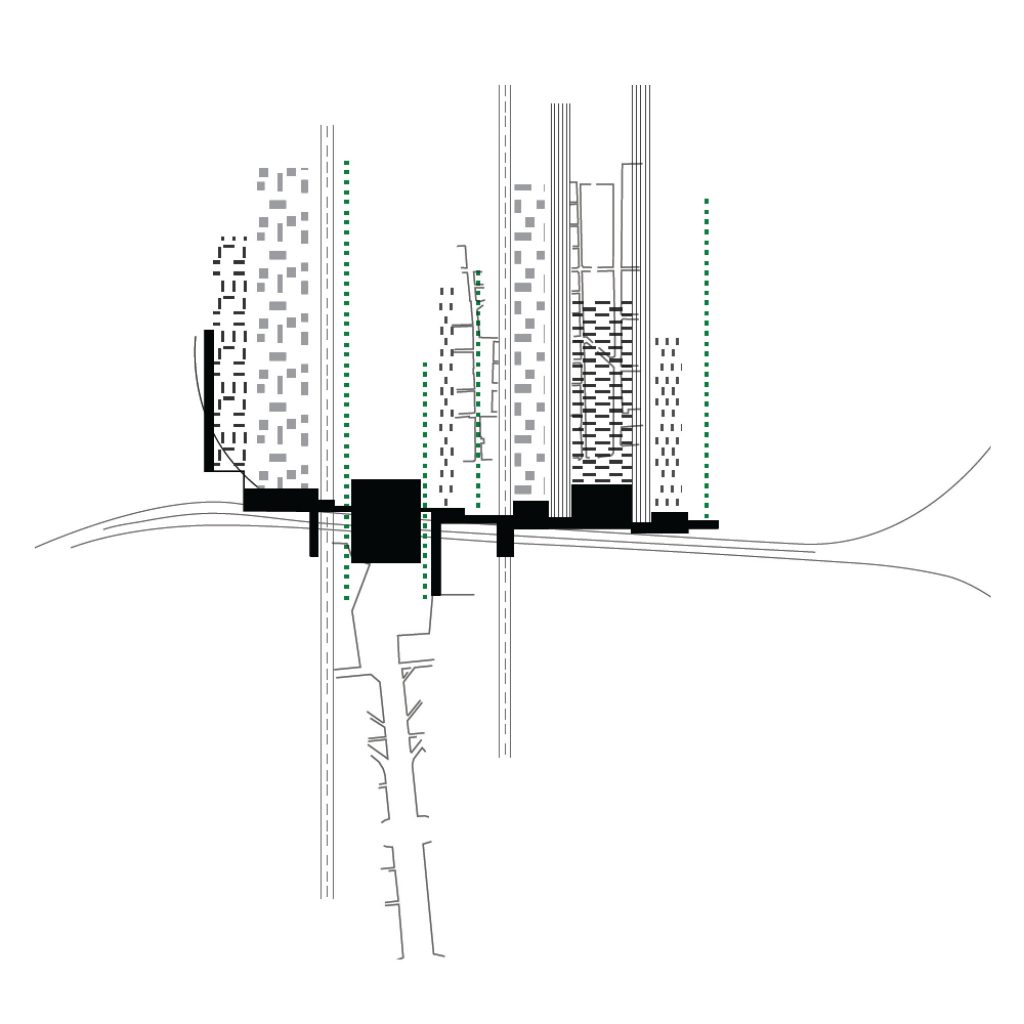

Mathematics as the element that structures (not always explicitly) the form, making it recognisable, for centuries has organised this invisible framework through discrete measures, proportions and modules. Now, the complexity of the contemporary built space, and not only of its most iconic architectures, seems to require a leap in the quality of the instruments that allow its readability and modifiability.

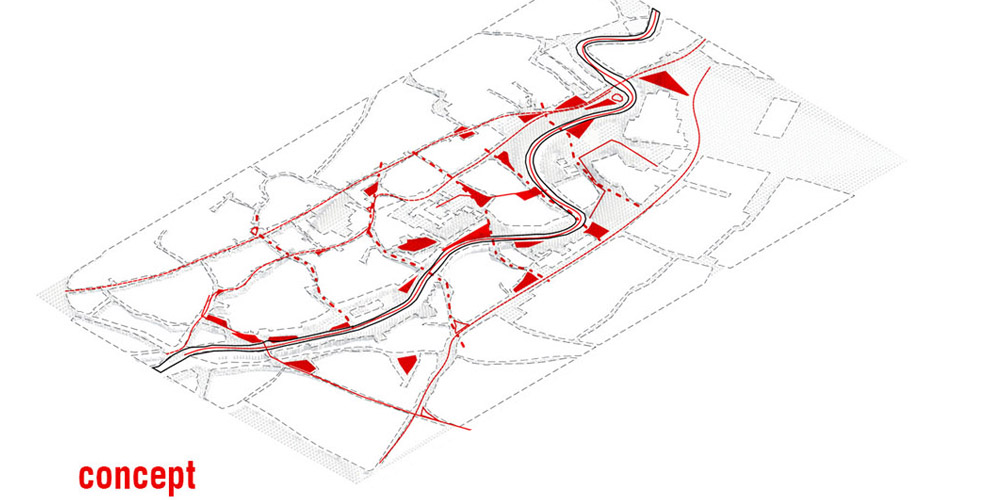

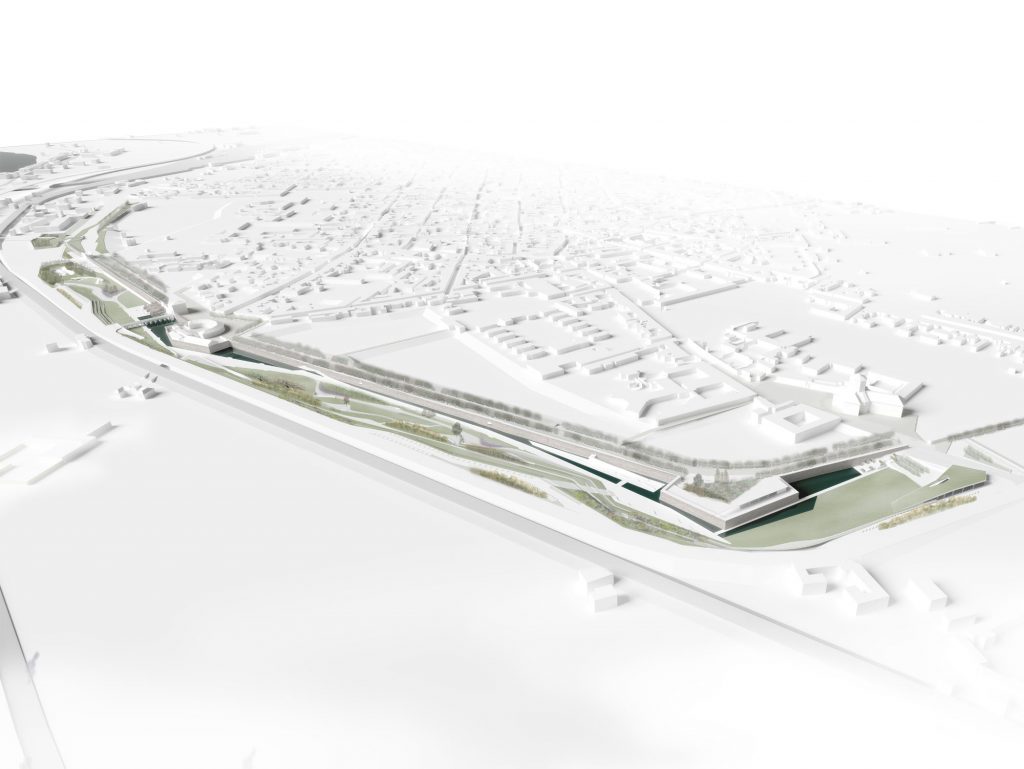

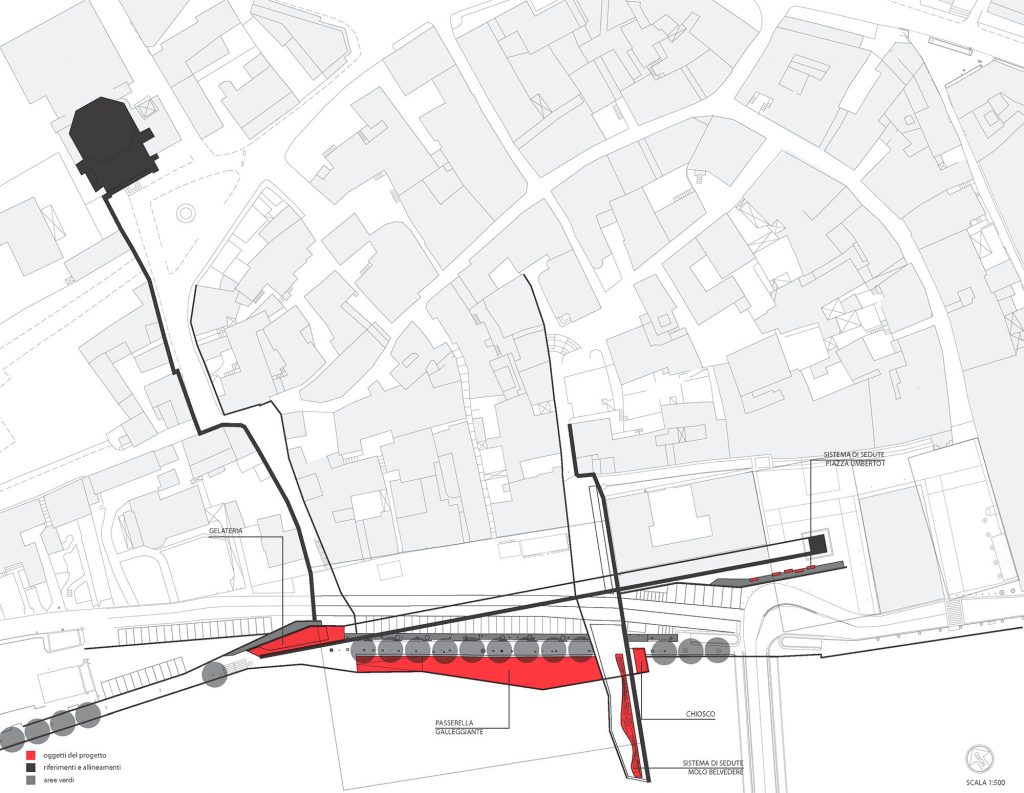

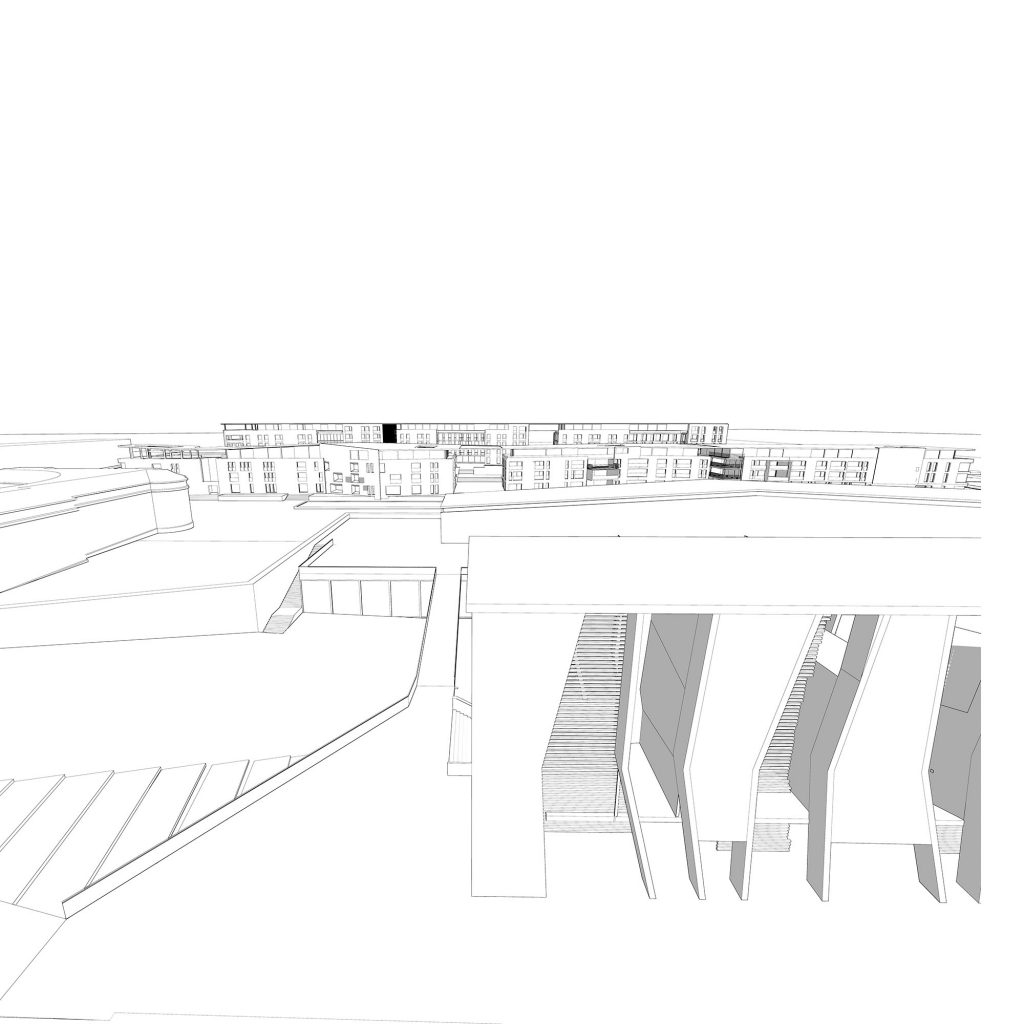

In the past, space was read and organised on the juxtaposition between the city and the countryside and on their peculiar measures. In the reality of urbanity today, the thresholds between the different parts that form it are rather describable as blurred surfaces readable through the concept of continuity and varying intensities. In this new dimension, the ground, as a thick modified and modifiable surface, maintains an essential role to organise a possible readability of a space that otherwise struggles to find its references.

These themes are addressed from a technical point of view, understood as the necessary knowledge to imagine and make an idea designable. Technique (téchne) therefore, must confront with the digital instrumentations where mathematics and measures are inflected as algorithm and modality of variation.

This book is a reflection that, with the benefit of practical examples, proposes to reason on the relationship between an idea and its representation, between a sketch, analogical and digital models, and on the “mental” tools which manage this relationship.

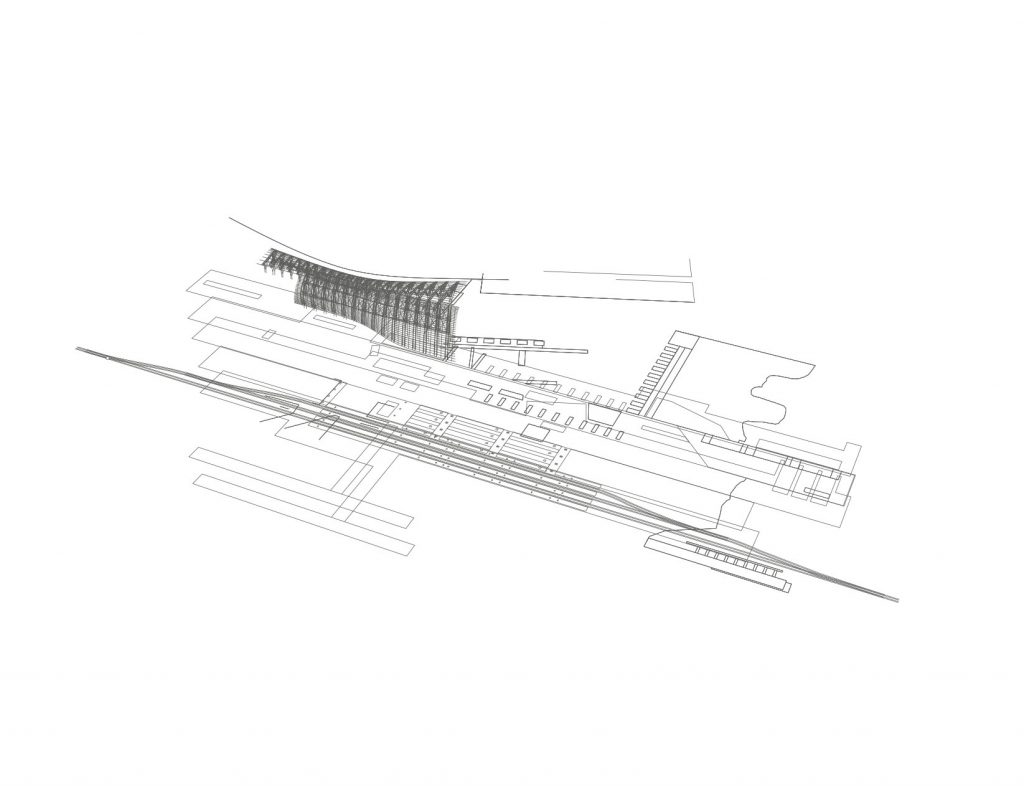

It is furthermore a reflection on the theoretical and practical implications of the concept of fold, or better, on the act of folding, as a concrete and tangible capture of the infinitesimal that directs a tectonic possibility. To do this, to try and control the infinitesimal as a measure that gives structure to contemporary design, a delving into mathematics as the algorithm that manages the machine, was necessary.

This publication is based on the doctoral dissertation in Urban and Architectural Design presented at the Politecnico of Milan and on the research and teaching activities developed by the author in that school and, subsequently, at the University of Cape Town.

Contents

Acknowledgements 6

Preface 7

Foreword 9

Introduction: measures and scales of the contemporary city 13

The Renaissance: measuring and touching the infinite on a plane 27

Readability and designability of the contemporary environment 43

A method: touching the infinitesimal 61

Conclusions: possible applications of a method in the contemporary space 113

Appendix: bridging urban disconnect 139

Bibliography 148

_

Foreword

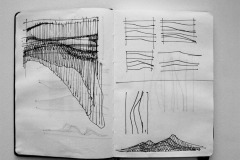

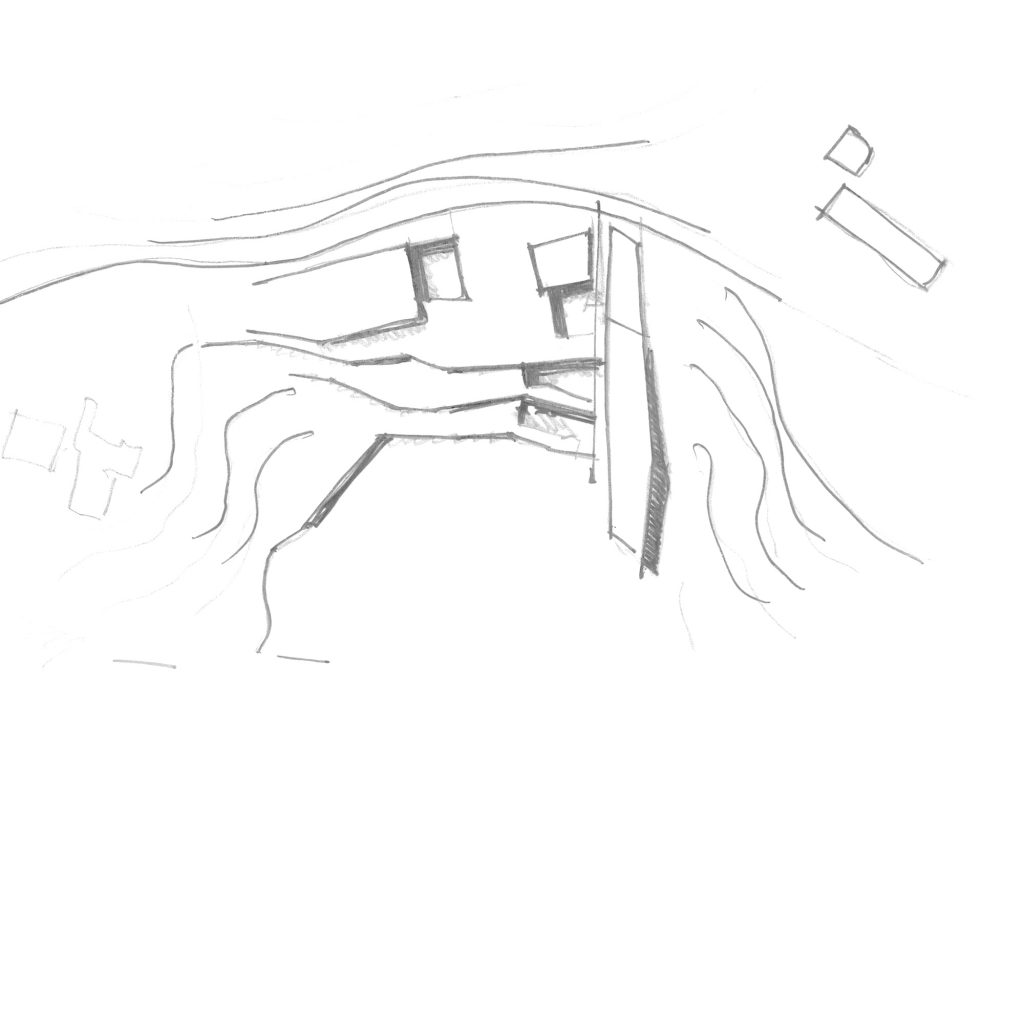

I see Matteo Fraschini now as he was then: young and carefree, working with his student, Matteo Graziani, on a metal mesh manipulated and moulded according to the sketch, a wise compression of the three dimensions on a flat surface.

Thus, the young teacher, already a professional architect, tested with his pupil, an expertise later displayed in the projects for Segovia and New York. He placed in his student’s hands the mature result of the work just created, in a constant and careful application of the design tools.

Therefore, it comes as no surprise for me to see this book bringing today to its completion a process that began at that time, was honed during Fraschini’s PhD Thesis and continued in his most recent South African years with new students. For them, in this book, Fraschini perfected the study of the architectural tools that he has developed, based on specific theoretical and historical preconditions, for his teaching activity.

On my part, I would like to take this opportunity, as a witness of his journey, to say something about what connects him to the School of Milan, of which I became, in fifty years of work, a representative. I clearly see Matteo Fraschini taking over the baton in the relay race between generations. A baton that he will carry on in his South African journey at the University of Cape Town with a new generation of students that will demand from him new original contributions pointing towards directions currently unknown.

I remember myself when, at the same age he is now, I was studying the instruments of an architect, which were based on technical drawing for the architectural design: Borromini’s tables for the Opus Architectonicum. For me, Monge’s descriptive geometry as well as Futurism found an ancestor in that book.

The projectivity, created by Alberti on the basis of Brunelleschi’s mirror discovery, found in the Opus Architectonicum a systematic application into design. On the other hand, the Milanese artists of the beginning of the last century, the Futurists, could find a pioneer precisely in the matter modelled by the construction. I will not go further into the concept.

If, at the time, the topic was the planar surface and the geometry that directs it, today, it is the computer screen and the program behind it.

As reference I had Bramante and Leonardo, who were inspired by Alberti and Brunelleschi and followed by Palladio (and then Descartes). It was not a matter of resurrecting the past, but rather of the future finding a ‘language’ (to use a trendy metaphor) to display the data of an imagination freed from arbitrary acts.

Even though Palladio has been the master of post-medieval architecture, the four books of architecture could not have been written without Alberti. However, I also know that Palladio’s legacy is founded on Bramante’s Tempietto in the cloister of San Pietro in Montorio, just as I know that, without Leonardo, an evolution of the Platonic concept of the Idea into a visually based modern science would have never occurred.

Therefore, today, as an architect from the Politecnico, I claim a scientific dimension in the making of art, especially in architecture. I think about an art that knows the technique, its tools and machines; I think about the power of all the tools that have been crafted working together with the designing mind in order to orient world phenomena toward the definition of inhabited spaces.

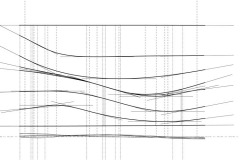

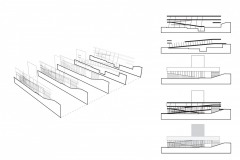

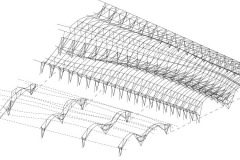

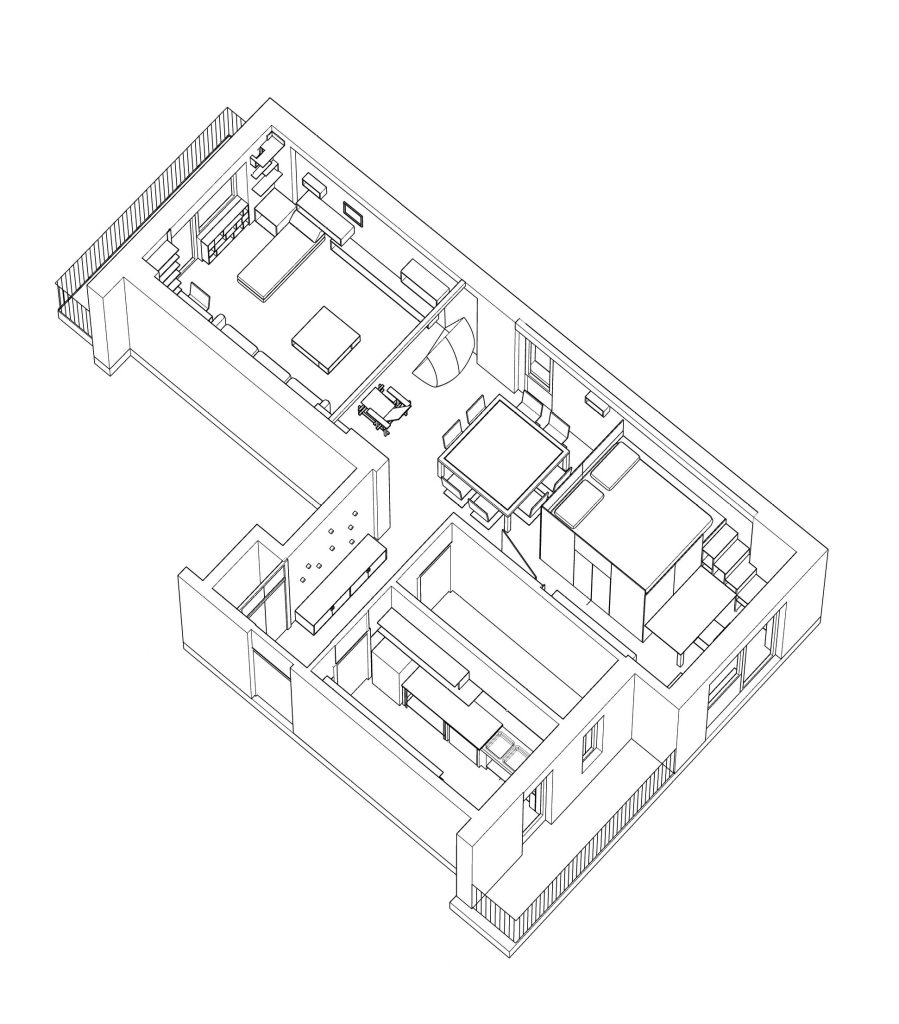

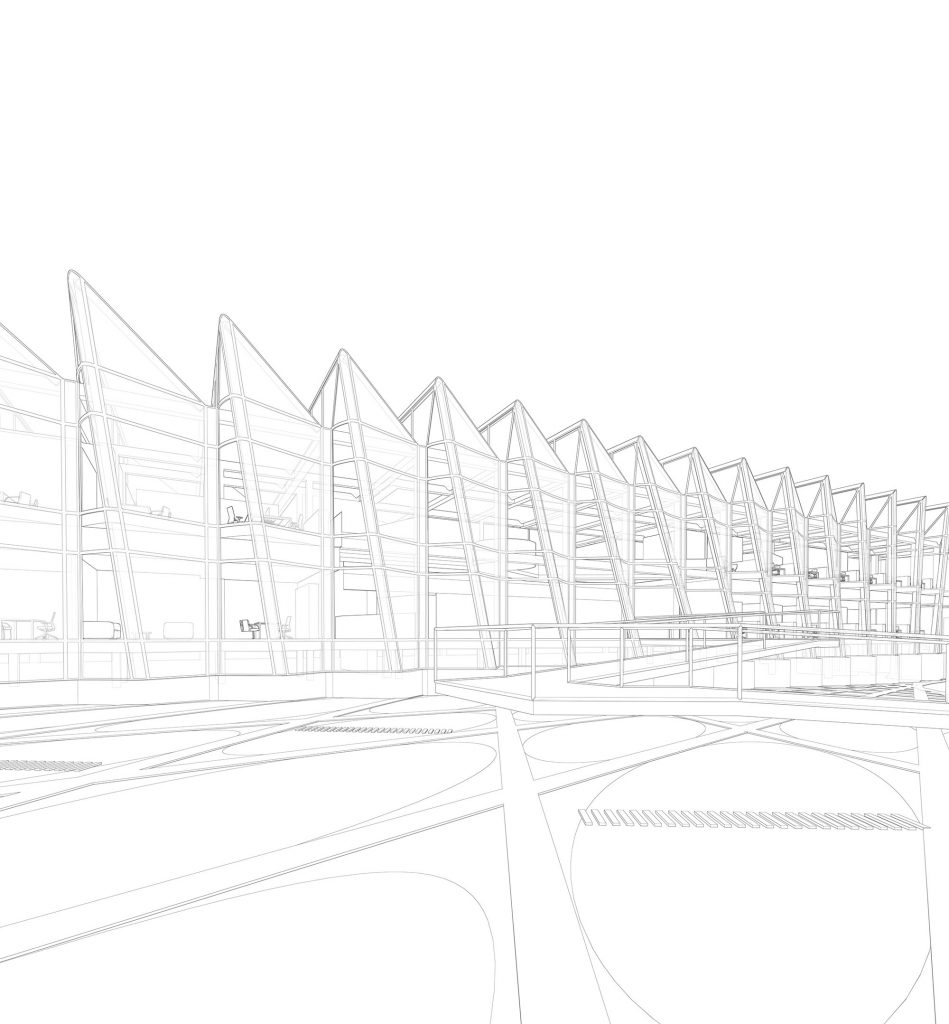

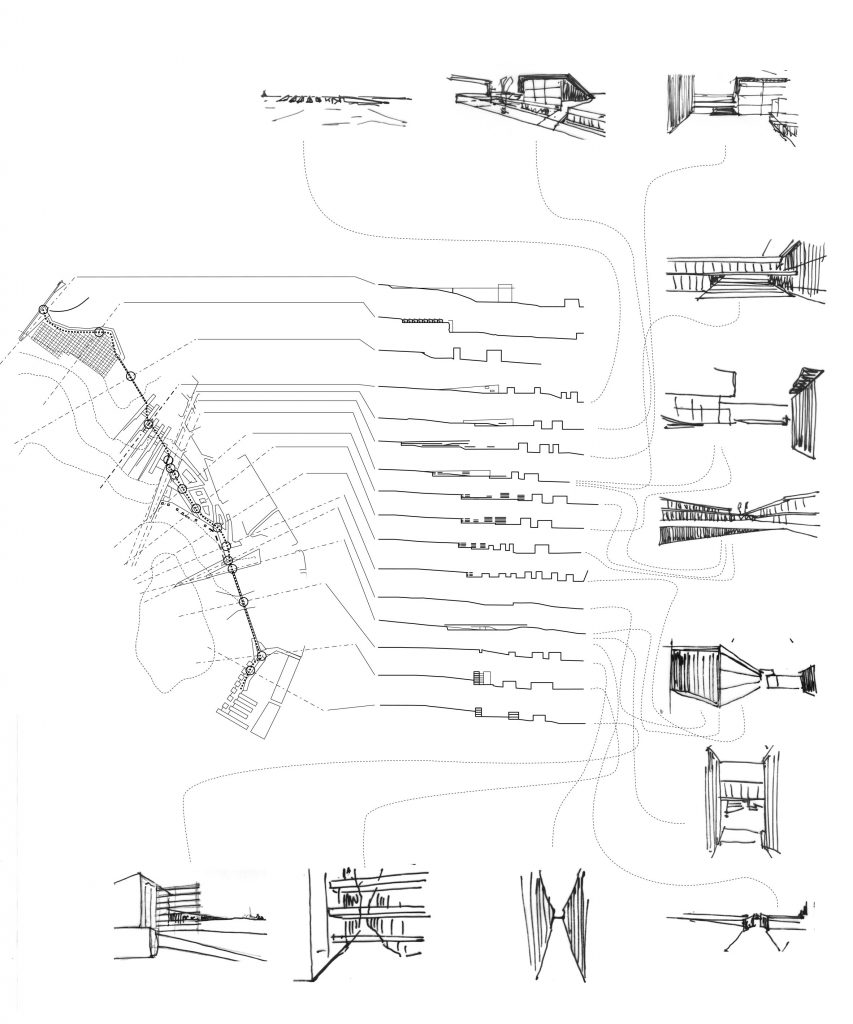

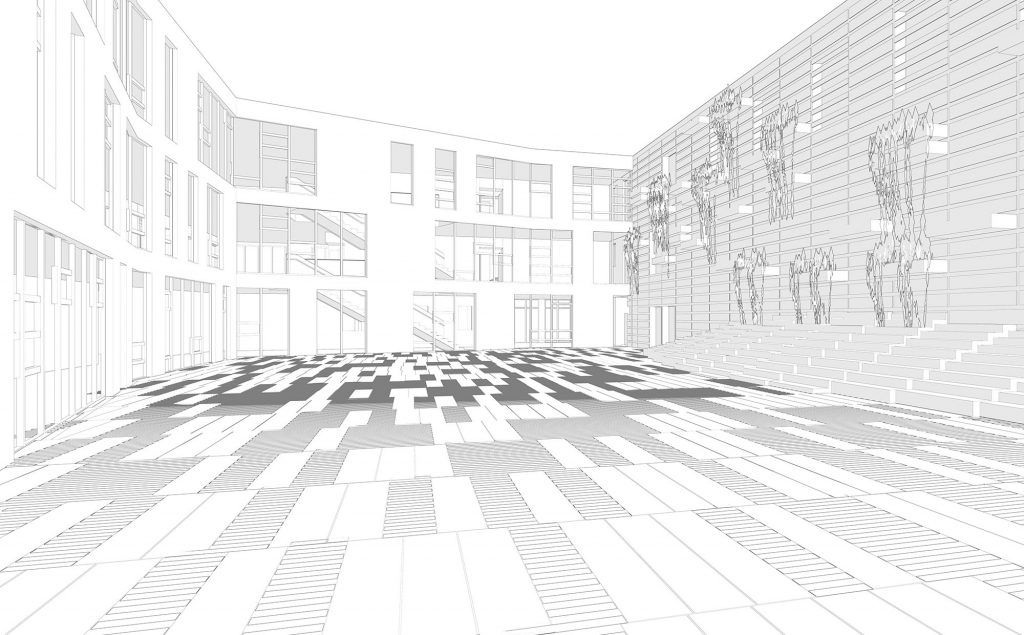

Fraschini went further. Starting from a centre of urgency of his own, the theme he tackled has been the tectonic of architecture. He deepened this topic, having clear in his mind the issue of architectural and urban design in the digital era. In this context, the main tool could no longer be the technical drawing. Instead, it was rather the relationship between a sketch, a digital diagram, the sheet of mouldable mesh, intended to explore a ground surface or a roof. It was the analytical and infinitesimal geometry employed to control the digital design software. The two-dimensional figures could then be operated ‘three-dimensionally’, as they are automatically projected on the surface of the computer screen.

This book represents the first effort to gather the results of more than a decade of research in order to provide young students with access to the tools of architectural design on an urban scale. It offers the lens of parametric digital design to deepen and refine a morpho-typological approach. Furthermore, it provides landscape urbanism with innovative and original contributions for the definition of a method that can discipline the design of the ground not only on its surface, but also in the strata involved in human construction.

I will not go beyond the scope of a preface. I would simply like to describe the path travelled by Fraschini from his Master thesis to his PhD, up to today and of the novelty of the theoretical and practical approach he developed, as originally as I just described.

Authors he admired in the late nineties, and in particular the work of Rem Koolhaas, Peter Eisenman and Frank Gehry, clearly inspired his theoretical and historical studies. From each, he drew specific questions to ask himself as a designer. I will summarise them as follows:

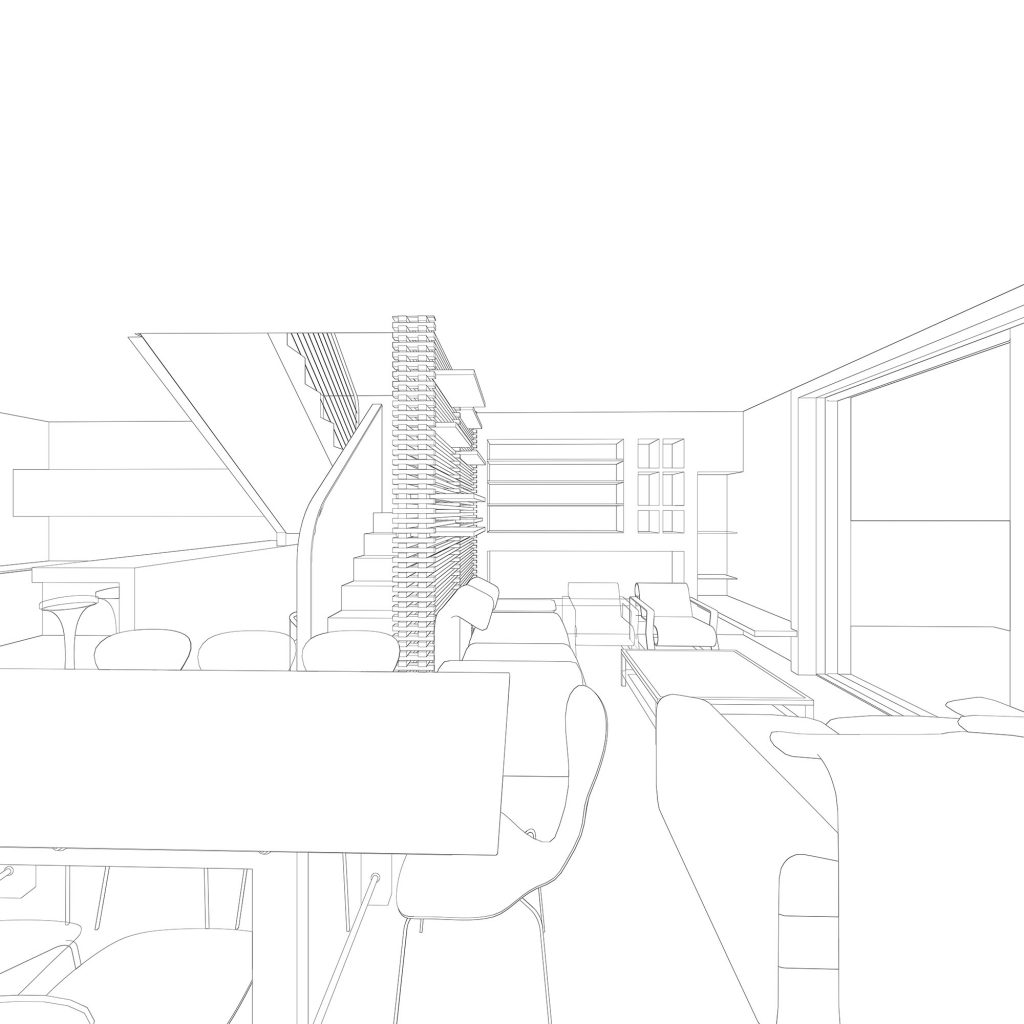

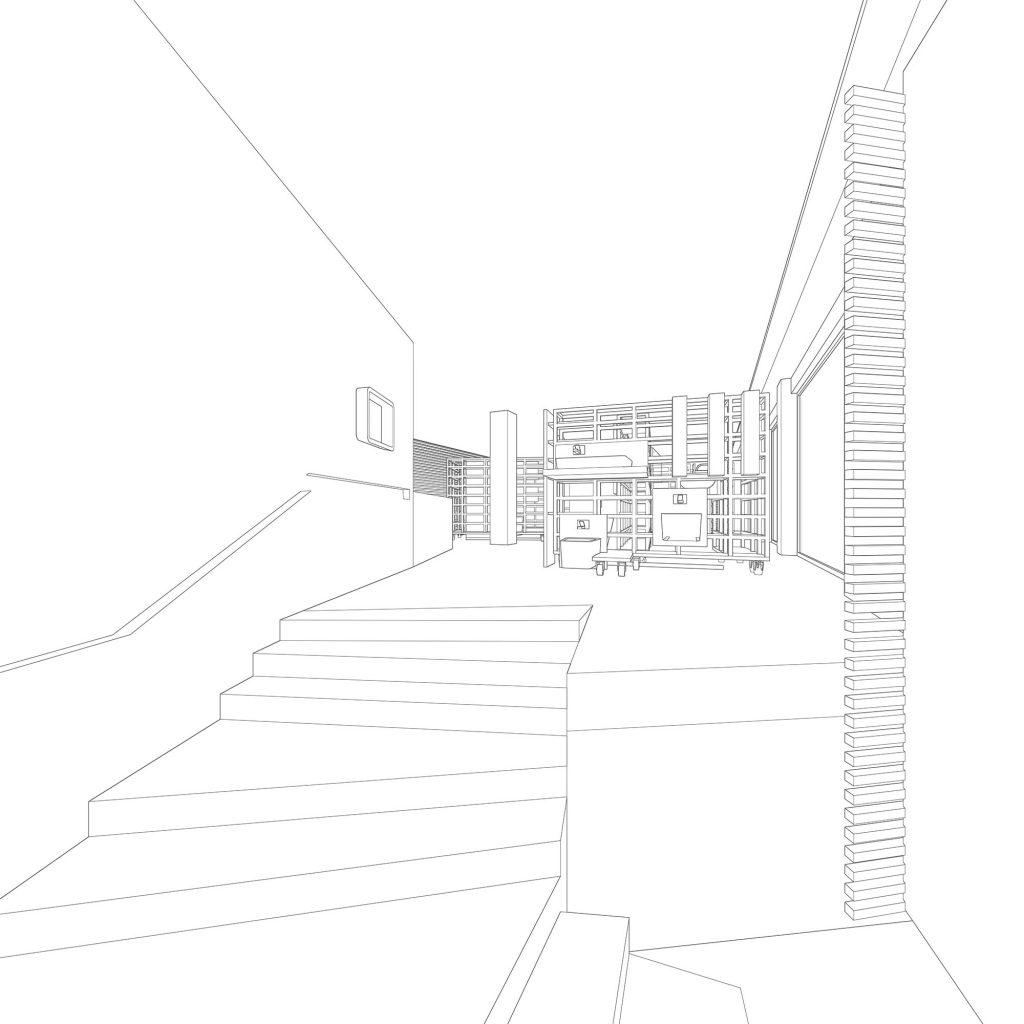

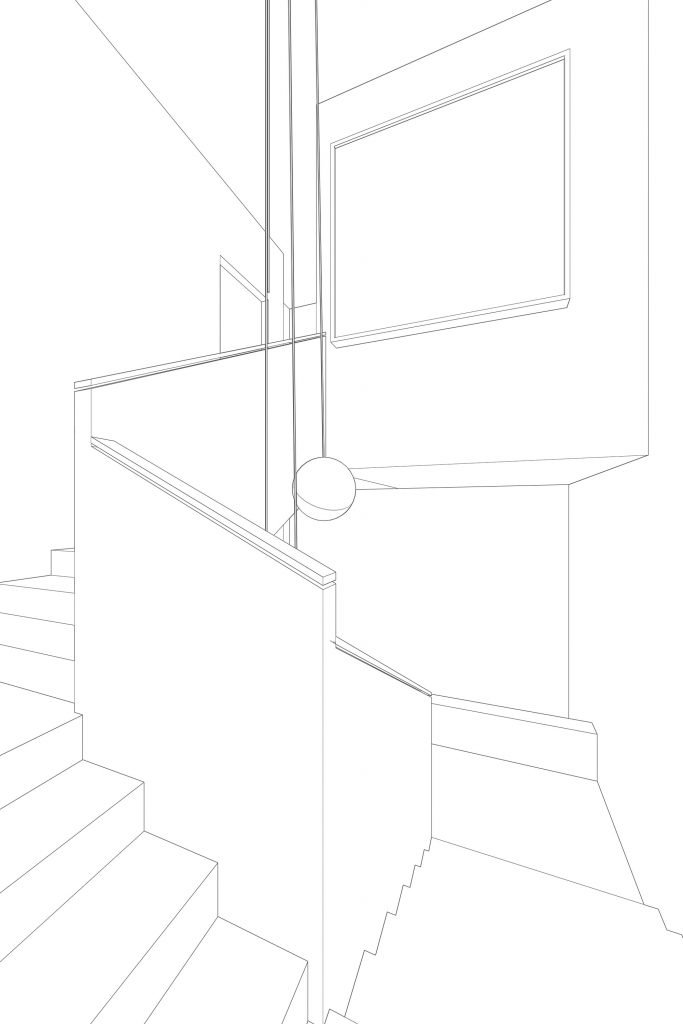

How to describe the constructive three-dimensionality and/or the spatiality that is modelled by means of architectural drawings?

In this question, the substantial two-dimensionality of technical drawing and of the flat projection, laid out on a computer’s screen, represents a challenge for the designer that is aware of the real three-dimensionality of what he designs to be inhabited and used.

Along this path lays the crucial question about the limits of the design tools in relation to the knowledge applied in the construction process; it is a knowledge where the transparency of the visual, which stops at the surface, is inadequate.

This question triggers the next: How could architectural design as a discipline overcome this gap and what constitutes the going beyond of the traditional designing instrumentation?

In this question, a speculation on the Cubist transparency post Le Corbusier and Terragni as a dilemma on the ‘canonical’ in relation to the Zeitgeist of Modernity has played a crucial role to link the Palladian legacy to the discoveries of the contemporary age.

In conclusion, a third question arises, more intrinsically connected to the ontology of architecture, that opposes transparency and tectonics as conditions of existence. A design thinking implies the overlapping of steps that are completely abstract with moments where perception, memory and imagination are activated according to different modalities. How can this dialogue be clarified, displayed and shared as an operative process?

I believe that this third question is the synthesis to which the others converge. Therefore the very core of this study is the innovative relationship between the sheet of paper, where the sketch is traced, and the metal mesh, modelled by hand into folds, curves and cuts. An infinitesimal geometry translates these modelling actions into three-dimensional forms, such as the ground or the roof-scape, to create the footprint/scenario in which natural or artificial inhabiting phenomena will take place.

To conclude, I find it very interesting to conceive the analytic geometry as a moulding, and therefore tactile, experience, translating the modelling process of the mind into something concrete. At the same time, the idea of looking at the manipulation of the metal mesh as a starting point for an abstraction process operated by means of analytic geometry is worthy of attention.

In my opinion, the tactile side of analytical geometry and the abstraction reached starting from the metal moulded mesh, are necessary implications of the coexistence of the abstract and the concrete in the digital parametric design. The reference to contemporary authors and old masters is essential to grasp the novelty of the questions and of the answers within the Zeitgeist of our own contemporary age. Similarly the reference to the design projects is a useful testing exercise for a public assessment.

Ernesto d’Alfonso*

_

*Ernesto d’Alfonso has been, for several years, full professor and director of the Ph.D. School of Architectural and Urban Design at the Politecnico di Milano. During that time, he envisioned and directed the ARC journal, a meeting point and a space for dialogue to the Italian Ph.D. Schools in Architecture and Urban Design. He published several texts, amongst others, L’Architettonica Commedia secondo Claude Nicolas Ledoux, Architettura, and, more recently, Il tipo – Itinerario teorico and L’antico, il Moderno e il Classico for the Quaderni di Arcduecitta’ series. He is the founder and director of the web magazine Arcduecitta’ (arcduecitta.it), which promotes and facilitates a critical debate on Architecture and Contemporary Urban Design.